A discussion on bidding.

MARCH 10 / 11

I will have a presentation at the ready, and we will look into the fine art of bidding a photography gig.

Small clients / Larger clients.

Bring questions and comments. Bring situations if you have them.

PREPARING A BID:

It all starts with a phone call or email.

“Can you send me your rates for — .”

And we begin to try to figure out what they want to hear from us. And when we do that, we are wrong. Never answer that question until you have had some time to analyze and put some thought into what this gig will cost you in time / production / assets.

Before we can bid a gig, we need to know much – MUCH – more about it than what they have usually offered.

You need clarification on this job unless you can answer this question; “How long is a piece of string?”

A phone call or email back will do one of three things:

- make the client uncomfortable because they have no idea what they are doing or asking for

- make the client realize the complexity involved and begin to rethink what they are doing (mixed results)

- make the client realize that you are a professional and approaching this thing professionally. (good results usually)

The first thing I do is look at what they are requesting. Analyze it carefully.

Are they a mom & pop business or a large corporation or agency? This can have a direct bearing on what we charge them. Smaller clients use the images differently than large corps or agencies so the value of the image changes.

You must decide a creative fee based on your understanding of value of the work, what others charge for same work, and how your work can advance their needs.

The Rosh Sillars article on pricing is a great way to get familiar with the per shot / per day way of bidding. Read it if you haven’t yet.

But even more importantly you must be ready with the knowledge of what is available for production in your area.

Will you need a digital tech for this shoot? If so, do you know one? Better find one now instead of waiting for the need.

Will you need any additional non-photographic assistance (booms, cranes, scissor lifts, water access, special lenses/gear?)

Will you be responsible for the hiring of models, caterers, model builders, set builders, mechanics, lift operators etc…? Or will the agency be responsible for those items?

Who at the client side will be approving what you shoot? There must be someone there to do it, or you are shooting blind and may have a serious problem on your hands that could destroy your business.

What about post production? What will the be expecting from you, and what is the time frame for delivery? Can you do that?

Gear rental. Many photographers rent their gear to the client if they are a big agency or corporation. Small business probably doesn’t get that bill. Why? Because agencies have built it into their system and small businesses have not.

Before we get into the actual bidding we need to know what we are going to be responsible for, and how it is going to be paid.

Consider what would happen if you suddenly got a big, BIG, job from a local ad agency.

You are signing 5 model vouchers for full days work ($1200 per model – $6000)

MUA and assistant are $1400 for the day,

You are paying a digitech $1200.

Assistant $400

Second assistant $300

Catering $1000

Wardrobe and assistant $2000

Location rental $900

Light rentals $500

Miscelleneous expenses $500

You are into this gig $14,200 and all of that money is due in 30 days or less.

The agency is not going to pay you for 90 days.

You have a problem, and if another big gig comes onto your plate, you may not have enough cash (or credit) to afford to do it.

In other words, success can kill you dead – fast.

This is where being firm and getting advances, payable guarantees, contracts and such are so important.

And knowing who and what costs are associated will help you get these numbers together faster, with less stress than if you are running around doing research you should have been doing a long time ago.

- Do you have access to a modeling agency?

- Do you know a digitech?

- Do you know and work with a good MUA?

- Do you know a retoucher who can work your files if you need them to?

- Do you have a list of caterers?

- Do you know any assistants in your area – and what they charge?

- Where is the closest place to rent gear?

- Do you have an account there?

- Can you get all the info you need at your fingertips before you start the bid?

You MUST have this information at the ready.

Because it takes more than a few hours to do.

Because if you do not have those numbers you cannot bid the gig.

Because you do not have time to do it when the time comes.

START putting these numbers into some sort of list so you have names and ballpark numbers to help you along with the bid.

WHAT TO DO WHEN THE BID GOES AWRY

FIRST OF ALL, DO NOT PANIC.

These sorts of things happen all the time. The client gets new mandates from their client, or the packaging is sent back from the legal department, or they may have decided to go in another direction or add images or go on location or, or, or…

It is NOT a big deal, you just have to be ready to face it head on.

That means not only having all your ducks in a row, those ducks are pristine and ready to perform.

One of my fellow photographers describes his method as preparing for everything to go wrong before it goes right. And this is where the preparation we discussed above comes in really handy.

Usually things go south in one of three ways.

THE CLIENT DECIDES THE BID IS TOO HIGH

OK, we can deal with that. The creative fee is not to be touched, but if we have itemized everything on the bid, there are certainly some places you can make changes. Perhaps your assistant can double as a digitech. Perhaps a trip to Subway or a local pub for lunch instead of a catered set. Perhaps the client can furnish people from inside the organization for the talent in the shoot. (We did this with a shoot for Peoplesoft. They wanted 25 different people and the modeling agencies in San Francisco were nearly $100,000 for the buyout the client needed. So they recruited in-house and we shot the employees who got Giants tickets and a dinner out of the deal.)

Perhaps there are other ways.

But we have prepared for this because we line itemized every single thing in the bid.

“Yes, we can lower the bid. Let’s find some places make some changes together.”

This reminds the client that you did not just fabricate a number out of thin air, there are real costs attached to making images like the ones they are looking to create. Making them be a part of the process also shows them that you are willing to find ways to make this work, even if you do not get everything you originally asked for. Knowing that it costs what it costs is a great way for the client to understand the complexity of the work to be done.

If the client simply doesn’t want to be involved, then you must press them on what number they want to reach so you can figure out how to make excellent photos for that budget. If they are unwilling to give you a target, then it may be a good time to walk away. This sort of brinksmanship tells you a lot about what it will be like working with them… and it ain’t good.

THE CLIENT ADDS MORE TO THE PROJECT

We call this tactic “scope creep” and it can be tough to deal with when it comes up before the shoot, and even tougher to deal with when it happens DURING the shoot. One of the reasons I like Rosh’s ‘per image’ approach is it makes scope creep very simple for both to see and understand.

“I was wondering if we can add two more shots to the Thursday afternoon shoot,” says the client on voice mail.

“Not a problem, Bob, i will amend the proposal to include the two additional shots at our agreed to rate of $300 per. Coming your way in an hour.”

If you are not doing the per shot approach you can see how this may be difficult to counter. They are paying you for a day, and they want you to make two more images in that time frame. How do you counter that? Unless your contract is a per-shot / per-day rate, you will have a challenge in refusing the extra image requests.

On set it usually comes like this; “Hey, Don, since you have your camera out, can you run over to the office down the hall and make a few shots of the new copier machine?”

“No problem, Art, let me get you a “Change of Work Order” and we will get those shots right after lunch.”

You agreed to $300 per shot, so if they want four more shots, you add $1200 to the contract/invoice. This is usually fine with the client since they agreed to the per shot pricing and they can budget and justify the expense. Occasionally you will find that enthusiasm for the new copier portrait fades rather quickly.

YOU DON’T HEAR BACK FROM THE CLIENT AFTER THE BID

This can be tough. We put so much thought and effort into making the perfect bid, and now we hear nothing?

Do not let this stand. After the appropriate time you have decided on, you must call them and ask them what was wrong with the bid.

“Hi Art, it’s me, Don Giannatti, and I am wondering what happened to the bid I gave you on the “Train Your Alligator at Home” packaging project we bid last week. Do you have any questions?”

If they do, then answer them and work it out.

If the project went to someone else, then ask what you could have done to make your bid more acceptable. Most of the time you will get an honest answer.

Perhaps the client decided on a different aesthetic direction, or the bid you proposed was too high.

Or too low… yeah, it happens.

Or maybe they haven’t yet moved forward with the project and all those 8 days of fretting on your part was because the project manager decided to wait until after he got back from his Paris honeymoon before pulling the trigger.

In any case, you should know and realize the options in front of you.

Never accept that you were overlooked without finding out IF you were, or if it was something else.

It usually is something else.

As I say nearly every day – this business is a numbers game and getting your info in front of as many people as possible is what wins.

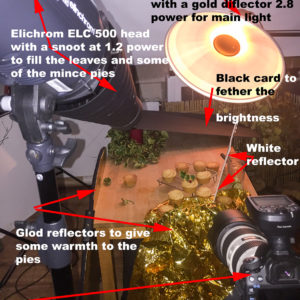

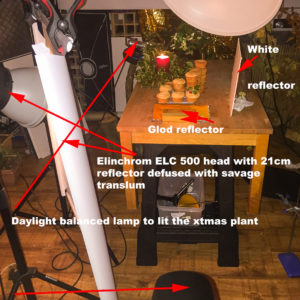

IMAGES FRIDAY

IMAGES SATURDAY

FRIDAY ADVANCED

SATURDAY ADVANCED